Slums, Crime and Seven Dials

Poverty and crime in Covent Garden

By Nigel T Espey

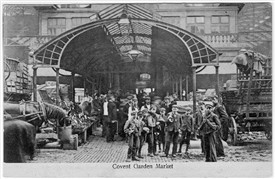

Children used as casual labour in Covent Garden Market. 1915.

Copyright Westminster City Archives

Poverty

19th century London was the setting for abundant poverty. The Victorian era clearly defined a division of class types: “working men,” “intelligent artisans,” and “educated working men", though of course class divisions were not so neatly distributed. The abundant poor stagnated while the city left them to themselves, and even those who considered themselves respectable working men barely made enough in a week to pay their rent and provide for their families.

In many respects the Covent Garden of the 19th century was reminiscent of the developing world today. The poor swarmed around London, taking what jobs they could find, many of them unpleasant. Casual work could be picked up and dropped as and when the opportunity arose. Men could readily find work as porters, boys could hold horse reins, girls could buy and sell flowers. If no casual work could be found in the area, the proximity of Theatreland made it a good place to beg.

In 1834 the Poor Law Amendment Act was passed to address the poverty problem. It was believed at the time that the old law, the Poor Law of 1601, contributed to overpopulation by coddling the poor, providing them with everything they needed, thus freeing up their time to reproduce.

The outraged middle class, newly-equipped with the vote, were determined to stop this perceived threat, and in doing so lessen the amount they paid in rates. The Poor Law Act of 1834 was their instrument. It replaced the old poorhouses with new workhouses that had appalling living conditions. People who had lost all other prospects had no choice but to go to the workhouses, and many of them were turned away. Families who went to them were often broken up and people were often too weak or malnourished to keep up with the back-breaking work they were required to do there, such as breaking stone or oakum-picking.

In 18th and 19th century London, spaces to build workhouses in central areas were hard to find. The workhouse that later became the Strand Union workhouse in 1836 perfectly illustrates the brutal pre-transition into the Poor Law Act.

Formerly belonging to the parish of St Paul Covent Garden, the Strand Union Workhouse was built in 1778 in Cleveland Street, just to the west of Goodge Street, on the site of a former paupers' burial ground. As the number of paupers rose in the nineteenth century, the building became seriously overcrowded and by the 1850s there were over 500 of the poor crammed into a very tight space. This overcrowding was inevitable as the area sucked in people looking for casual work in the market. They were able to find cheap lodging houses in the notorious slums of Seven Dials on the edge of Covent Garden.

Seven Dials

“...where misery clings to misery for a little warmth, and want and disease lie down side-by-side, and groan together.”-John Keats on Seven Dials

Covent Garden was no stranger to poverty and this was due to the slums of Seven-Dials. Confusingly named for its signature column with six sundials on it, today Seven Dials is famed for its mixture of niche shops and restaurants. However it was once known as one of the great slums of London, rivaled only by the nearby St Giles’s Rookery. The construction of its buildings in the 1690s was the result of a speculative failure and so they were not of sufficient quality to prevent deterioration. Almost naturally it became a site for cheap lodging. With Covent Garden Market close by, Seven Dials attracted hordes of unskilled labourers.

The living conditions were terrible. There was overcrowding and children swarmed all over the place, the houses were packed and filthy, the shops sold only second-hand items and lodgings struggled to keep up with the basic needs of their tenants. William Hogarth is even thought to have derived inspiration for one of his famous prints, Gin Lane, from Seven Dials.

The character of Seven Dials was such that it garnered both disgust and fascination. Charles Dickens was quite taken with it, and the things he saw in both the slums of Seven Dials and St Giles Rookery are believed to inspire Night Walks, an essay he wrote to convey the ominousness of walking London’s streets at night; the feeling of how easy it was to stumble from a safe neighborhood into a baleful slum. John Forster, Dickens’s biographer, critic and friend, recalls a young Charles Dickens’s fascination as a “profound attraction of repulsion” whenever the boy ventured near a slum.

“If he could only induce,” writes Forster, “whomsoever took him out to take him through Seven-dials, he was supremely happy". The inspiration he drew from London slums like Seven Dials explains the mix of dark and light themes, ranging from poverty to opulence, in books such as Nicholas Nickleby.

“Good Heaven! What wild visions of prodigies of wickedness, want, and beggary, arose in my mind out of that place!”-Charles Dickens

John Keats perhaps put it most poignantly when he called Seven-Dials the place “where misery clings to misery for a little warmth, and want and disease lie down side-by-side, and groan together.”

Crime

“The walk through the Dials after dark was an act none but a lunatic would have attempted.”- Donald Shaw

Where poverty abounded, so too would crime, though it was not always causal.

Covent Garden, and especially Seven Dials, was said to be so dangerous at night that people often hired sedan chairs to avoid having to walk out in the open. It was an expensive charge, but with four chairmen and a lead boy, it left the customer usually free of molestation.

The greatest night-time threats were the various gangs that made their home in Covent Garden.

Pickpockets were abundant, and were one of the chief reasons why sedan chairs were hired in the first place. The most notable pickpocket gang to frequent Covent Garden was led by a woman known as either “Jane Web,” “Jenny Driver,” or “Jenny Murphy.” Regardless of what she was actually called, or if she was, in fact, just three separate women, she was notorious for being “one of the expertist hands in town at Picking Pockets.”

But other than thieves and pickpockets, there were also the more violent gangs, such as the infamous Mohocks of the early 18th century. Unlike typical bands of desperate muggers or highwaymen, the Mohocks are notable because they were not composed of poor or even working class men. Rather, they were well-to-do young gentleman who terrorized people for fun. Often they would meet up at a club or tavern and, when they were drunk enough, would unsheath their swords and order everyone to leave, often proceeding to toss waiters out of windows or run tavern-owners through. From there the Mohocks would spill out onto the streets and indiscriminately attack men and women alike: brutalizing, mutilating and raping. Generally they did not attack unless they could be assured of their superior numbers. Though a bounty was placed on them in 1712, they were not decisively ended so much as their activity simply subsided.

In addition, there were as many as 22 gambling dens in Covent Garden in 1722. They were run with admirable efficiency, and spoke of criminal elements’ capacity for law-dodging; “squibs” were given money to play and attract more players, “clerks” supervised the squibs, “flashers” reassured despondent players, and “captains” filled the roles of bouncers. Moreover, people who warned the dens of approaching policeman would be rewarded for doing so with a guinea or two.

Police Force

Dating back to the medieval period, a group known as the Watch, or “charleys,” was the official law-enforcement group in London, and it was they who the criminal elements of Covent Garden initially had to contend with. They operated out of “roundhouses” from which they were supposed to emerge when trouble presented itself, and when they did catch someone, the suspect would be detained in the roundhouse to await trial until morning. Sadly, the Watch was typically perceived as useless and inept, unsuited to the bourgeoning social strata of growing London.

Print of interior of the Bow Street Police Office in 1808. published by Rudolph Ackermann.

Copyright Westminster City Archives

London’s modern Metropolitan Police owes its existence to the Victorian precursors that followed the Watch, known as the Bow Street Runners. Founded in 1749 by Henry Fielding, a famous writer, they were an official extension of the Bow Street Magistrate’s Office, which meant that, unlike other law-enforcement groups like the

thief-takers, they were part of, and funded by, the central government. Consequently, they were more effective as well. They regularly operated out of Covent Garden’s Bow Street, but they also travelled the country arresting offenders and solving crimes.

Though the Bow Street Runners disbanded in 1839, it was they who normalized and regulated many police practices emplyed by the modern police service today; the early manifestations of central government control on London’s street life.