Covent Garden Market Moves Out

End of an era

By Anne Bransford

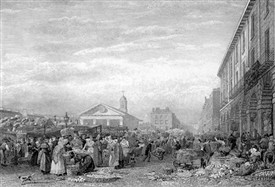

Covent Garden, 1726

Peter Angelis

The Market was just as much a mess in 1824 as it was over a hundred years later

Copyright Westminster City Archives

The hustle and bustle of Covent Garden Market in 1864

Copyright Westminster City Archives

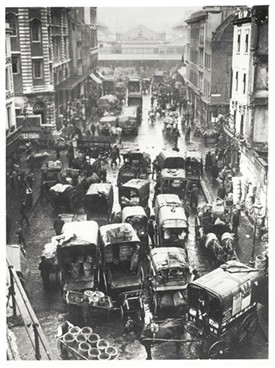

A view of Russell Street circa 1900 - it's easy to see how crowded it was even then!

Copyright Westminster City Archives

An empty Jubilee Hall, which had housed the Flower Market

Copyright Westminster City Archives

A proposal for the new site at Nine Elms, Battersea

Copyright Westminster City Archives

A view of the old Flower Market today

Copyright Westminster City Archives

Covent Garden Market has been central to London life since 1670, when King Charles II granted the Earl of Bedford a private charter to hold a market every day but Sunday and Christmas Day (this charter was passed down with the title). People from all over the city would gather in the Piazza, dominated by St. Paul’s Church, to buy and sell all sorts of commodities, both legal and illegal. In earlier centuries the area had been renowned for seedy activity – prostitution had come in with the market, and the theatre crowd made its home in the area – but by the 1900s the main products were fresh produce and flowers brought in from local farms as well as by boats along the coast. In the 20th century, products were shipped in from places like California, Marrakesh, and Holland and trucked in overnight from as far as the border with Scotland.

Covent Garden was the premier price-setting market in Britain: at its height the market was the destination for almost a third of all the fruit and vegetables imported into the country. The annual turnover was about one million tons and the sale of all this produce is estimated to have been worth £65 million. A fifth of the produce consigned there was then shipped out to other markets around the country. An anonymous online commentator describes his experience of the market as a young man:

“The Garden, like Spitalfields and the Borough, were places where people worked bloody hard and in all weathers…I remember as a young lad in 1970 unloading onions off our lorries on cold winter nights – all around the markets untying ropes and soaking ice wet canvas sheets. It was hard graft but the night porters would be singing some Matt Monro or Sinatra ballad; the wonderful smells of fruit barrows on cobbles, Hessian sacks on lorry radiators, the old tea stalls, bacon and [hot] dog rolls – Heaven.”

The 1957 film Every Day Except Christmas documents what the market was like in a fantastically vivid and engaging way, allowing the viewer to get a sense of the hustle and bustle of Covent Garden.

Over the centuries the market had flourished – so much so that by the late 1800s the space could no longer accommodate the explosion of commerce within. Even after the construction of the Covered Market in 1834 and the Jubilee Hall in 1904, the market remained unsuited to the sheer volume of traffic. Maps of the time show the bottlenecks caused by the lack of access to the Strand and Long Acre. The Bedford Estate did what it could to relieve some of the pressure, but because of Covent Garden’s central London location there was precious little room to expand.

In the face of increasing public dissatisfaction (encouraged by the rise of socialist ideas) with the private aristocratic ownership of London’s, and indeed England’s, most important produce market, the 11th Earl of Bedford sold the entire Covent Garden Estate to the Beecham family in 1918. The new management of the market ran into the same problems that the Earls had faced. In 1920 there was an attempt to turn responsibility for the market over to the London County Council, but the sale was turned down for a recurring issue: lack of room for expansion.

The next attempt to solve the problem of the choked and crowded market was to consider its removal to a different site. A Bill of Parliament was introduced to relocate the market to a site at the Foundling Hospital at St. Pancras, but this was withdrawn in 1927 in the face of opposition from public, private, professional, and commercial interests. Left with seemingly no other choice, the Covent Garden Property Company (run by the Beechams) prepared a 1928 plan to attempt development, but even this was blocked. Rival developers in Spitalfield Market objected that the proposed alterations were in violation of the original 1670 charter. The events of World War II and post-war empty coffers delayed even further any attempt to solve Covent Garden’s problems. Sadly, business in the market was left to suffer for a few more decades. The quantity of commodities and thus the congestion flowing through Covent Garden had doubled between 1910 and 1929, and the market only continued to grow.

Finally, in 1955 the government set up a committee to look into the current methods of produce marketing in London and to make recommendations for improvements. In regard to Covent Garden, the committee advised the creation of a new wholesale market to free the old market from its burdens of over-crowding; the Covent Garden Market could then be reorganized with facilities more appropriate to its role as the central price-setting market in the UK. While this part of the recommendation was rejected, the need for a municipal Covent Garden Market Authority (GGMA) was agreed upon and in 1962 the market passed into public ownership.

One of the Authority’s main duties was to reduce fire risk, traffic congestion, and the volume of produce passing through the market while simultaneously increasing commercial exchange. To resolve this, the idea of moving the market surfaced once again. With the implicit support of Parliament, the Authority investigated the removal of the market to an alternative site, hiring Fantus Company International Division, to research possible locations. Initially, five sites were examined: Seven Dials (within the Covent Garden area), Nine Elms, Wood Lane, Beckton, and King’s Cross. The Fantus Company’s first report selected Beckton as the most suitable location for the new market, but there were objections from the Authority’s Market Management and Market Worker’s Committees. Then, British Railways made it known that a different site at Nine Elms would soon become available. All parties eventually settled on this location in Battersea.

Between 1964 and 1966, Parliament debated the Bill for the official transplant of the market. Finally, Royal Assent was granted on 10 March 1966 for the market to be moved by the early 1970s. Once this formal decision had been made, plans for the new market were developed. New Covent Garden Market was to be a 70-acre site (45 for fruit and veg, 16 for flowers) with its own Waterloo line railway approach, improved roads and lorry access, expansive loading bays, a 21-storey administrative building for offices of businesses involved in the market, and, most importantly, room to expand. In 1974 the Sheffield Morning Telegraph reported that nearly all the trading space in the markets had been let before the move, demonstrating high levels of excitement for new business opportunities in the improved space. The same article expressed a widely-held sentiment toward the move:“For reasons of commonsense and business efficiency, the old Covent Garden, partially the product of 17th century town planning, had to go, but a part of London life dies with it”. Philip Howard of TheTimes mourned that “the centre of London will not be the same without its sweet smell of ripe fruit, its strange vegetable night life, and those midnight lorries roaring in with a breath of the West Country, of Kent, and of the whole wide world”.

The market was relocated on 11 November 1974 and Covent Garden was left empty.

Brewerton, David. "Plan for Covent Garden about to Blossom at Last." The Daily Telegraph [London] 2 Aug. 1977: n. pag. Print.

"Nine Elms Site for Covent Garden." The Sunday Times [London] 8 Mar. 1964: n. pag. Print.

Every Day Except Christmas . Dir. Lindsay Anderson. Vimeo. N.p., Mar. 2012. Web. 3 Oct. 2012.

“Covent Garden Market”, Survey of London: volume 36: Covent Garden (1970), pp. 129-150. URL: http://british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=46106 Date accessed: 18 September 2012

Mackenzie, Andrew. "Just a Silent Finale for My Fair Lady's Tradition." Sheffield Morning Telegraph 17 Sept. 1974: n. pag. Print.

Howard, Philip. "Philip Howard Looks at London." The Times [London] 6 May 1970: n. pag. Print.