Geraldine Pettersson

On The Importance of Resident Consultation

An interview conducted by Audrey Chan

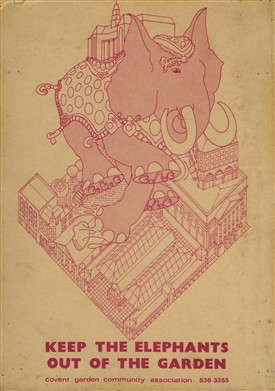

This sketch accompanied an important report that Geraldine worked on

©Covent Garden Community Association

As part of the Covent Garden Heritage Project, I had the pleasure of interviewing Geraldine Pettersson one lovely May evening at the Seven Dial’s Club. An economist by training with two degrees from the London School of Economics, Geraldine has written and presented numerous reports to the Greater London Council (GLC) Covent Garden Committee, as part of her work on Covent Garden. As she invites me to take a seat at her table, I immediately notice the impressive stack of documents and photographs she has with her. 'I've brought these to give to someone,' Geraldine informs me, and I can tell she has undoubtedly accomplished a lot through her work. Her firm belief in the need for simultaneously developing social housing and employment from tourism in Central London, coupled with an equally strong dedication towards resident consultation, made her an obvious choice when the GLC sought to bring in new staff to develop a new plan in the 70s focused on conservation in Covent Garden. Geraldine relates how she was appointed by the GLC 'to have responsibility for resident involvement', stressing that they needed 'somebody completely new'.

The necessity to bring in a new member of staff arose from an intense and seemingly irrevocable conflict between the GLC's existing proposals for redevelopment and the community’s needs. Geraldine describes: 'it was very much the town planning ethos, really, that people needed to redevelop city centres'. 'At that time', she continues, ‘the idea of people living in the city centre was not acceptable – people dismissed it, they thought people wanted to live in houses with gardens’. But there were many people who had lived in Covent Garden for years, ‘and they wanted to go on living there’, she asserts, also desiring ‘new housing to be developed’. To help me understand the conflict better, Geraldine pulls out from the pile a document illustrating the proposed demolition of historic buildings to make space for the proliferation of modern office blocks. This was a plan, Geraldine explains, drawn up by the GLC team prior to her arrival, depicting their intended redevelopments for Covent Garden – making evident why ‘nobody trusted the GLC’. Stuck at an impasse, the GLC brought in Geraldine ‘as somebody with responsibility to get the residents involved in developing the new plan’. From the outset, she identified how ‘there wasn’t social housing in the original plan’, and recounts: ‘we had to say to the GLC that yes, people do want to live in Central London. And they want to live in flats and not houses!’ However, ‘there’d been tremendous ill-feeling between the community and the GLC’ by then, she intimates, making her task all the more difficult as, for some time, ‘nobody would have anything to do with the GLC’.

Having effectively undertaken the role as mediator between the GLC and the residents, Geraldine set out to make contact with the Covent Garden Community Association (CGCA). ‘When I arrived,’ she says, ‘I realised I had responsibility to regain the trust of the community. And I thought, how can I do this?’ She describes how she ‘sat night after night’ with remarkable resolve, in what was then the Covent Garden Social Centre. ‘Nobody would have anything to do with me’, Geraldine relates, recalling how ‘everybody stayed away and said, “she’s from the GLC”’. Steadfastly persevering despite the setback, she believed ‘eventually somebody would talk to me’. This determination certainly paid off, as she goes on to recount: ‘John Toomey – he was chair of the CGCA – came over to me one night, and introduced himself. And he said, “I can’t bear to see you sitting on your own like this.” And I said, “Well, I don’t want to. I want to talk to you about your goal for the community. I had nothing to do with the old plan”’. This simple overture fostered ‘a good relationship’, as Geraldine tells me how he then introduced her to more people who eventually realised she represented a new approach with new objectives. It is tempting to regard this incident as a point marking the turn towards success, but Geraldine is quick to correct me, emphasising that it was really a ‘gradual’ process over time. It required much effort on her part and the people in the community before she gained their respect and trust, though she remarks: ‘I don’t think that necessarily extended to all the people who were in the Covent Garden GLC team’. When I ask how she managed to accomplish this, she readily explains: ‘what I did was to go out into the community and talk to as many people as possible, to have as many meetings as possible. I worked closely with the CGCA’, and attests ‘I was – and still am friends with some of the people I worked with’.

Once she had established a friendly communication platform with the community, Geraldine then helped enable a new planning process to begin. She reveals: ‘a lot of it was about asking them what they want’. Well aware that ‘people wanted new housing to be developed’, she and the rest of the team worked to have that included in the new plan. Citing the successful implementation of the Odham’s site development, Geraldine tells me how pleased she was when it went through: ‘I’m proud of the fact that we’ve got social housing in that development’. Extracting a bound report from the stack of documents – the final plan produced by the GLC – she says with a smile: ‘I’m proud about the fact that it was one of the best programmes of resident consultation’, adding that it was the only resident consultation exercise that won a gold award from the Town Planning Institute.

Geraldine warns, however, that this was hardly the end of the problems regarding the future of Covent Garden. Alluding part of her earlier success to her close working relationship with the then Labour administration at the GLC (which, she shares, gave her ‘extra clout’), she confesses: ‘it really changed when the GLC became Conservative again’. It was at this point that she left the team, admitting: ‘it was quite obvious that they didn’t want me to have anything more to do with Covent Garden’. She narrates how, much later, she had been asked by both the Westminster and Camden Councils to work on a review of progress with the Covent Garden Action Area Plan, only to have Westminster City Council withdraw the project from her (Camden Council, she is happy to say, insisted at the time: ‘No, we’re sticking with Geraldine’). Despite this change, her commitment to the cause did not wane., as Geraldine went on to do research work with the CGCA instead. Both influential and informed, she knew that the Conservative GLC had changed or wanted to change some elements of the Action Area Plan. The properties above the shops on James Street and Floral Street, she informs me, had been originally designated for social housing, but the Conservative GLC changed this element and allocated them for commercial use instead – ‘to be offices’. Showing me a report accompanied by a graphic sketch – captioned ‘Keep the Elephants out of the Garden’ – Geraldine regards it the most important report she worked on with Jim Monahan from the CGCA. She explains: ‘we were worried about the fact that now with a Conservative administration come in, they would change the plan’ – and they did. Armed with the research, Geraldine describes how the CGCA took the GLC to Court. ‘And I supported that’, she affirms, reminding me that ‘at the time, mixed use developments were thought to be totally unacceptable, not only to residents, but also to the commercial users’. A firm believer in its beneficial aspects (indeed, Geraldine has contributed research and a book on the topic), she maintains: ‘I’m always proud that it’s now acceptable for people to live in – and are happy to live in – mixed use developments’.

Inevitably, redevelopment comes with bittersweet consequences, as Geraldine concedes. When I mention the moving of Covent Garden market to Nine Elms in 1974, she avows that ‘it was a shock to everybody’s system because it literally happened overnight – it was there one day, and gone the next’, leaving just ‘empty shells of buildings’. ‘I know people felt the heart had been torn out of the area’, she sympathises, ‘because when the market moved, people thought, well, what is this, what’s going to happen?’ The evolution of the market space and the entire Covent Garden area has seen it transformed into ‘very much of a tourist mecca now’, and Geraldine points out how some current residents must feel they have ‘lost their sense of community’ and are somewhat alienated. ‘I do feel that it’s a lost opportunity’, she tells me, how commercial businesses don’t have ‘the slightest interest in the residents’. When I bring up the neighbourhood’s soaring housing rents, she attributes this partly to the introduction of the ‘right to buy’ scheme which enabled many units originally designated for social housing to be purchased by the tenants, and subsequently sold on the private market for much higher prices. ‘I would like, as always, to see more social housing’, she expresses, ‘but that can never happen’.

True to her roots as an economist, Geraldine’s opinion of the Covent Garden redevelopment is decisively ‘that it has been very successful’, though she is careful to add: ‘I know not everybody would agree.’ She brings up how London Transport had contemplated closing Covent Garden tube station, in the initial period after the market had moved in 1974. In reply to my disbelief, she assures me ‘we had a real fight to keep it open’, and rightly so, as she goes on to prove: ‘when I came here tonight, I had to wait ten minutes to get a lift up. And you think, it hasn’t got the capacity’. ‘I know some residents feel like it’s no longer their area’, she reiterates, ‘but it is Central London. It brings in huge amounts of business’. When I ask her what she regards the most important thing saved from redevelopment, Geraldine immediately mentions the historical architecture and built environment: ‘I do think that saving the buildings was a very important thing’. In her eyes, their preservation has added great value to Covent Garden. She contends: ‘I know families who come to London with their children, and where do they want to go? Covent Garden! And why not?’ She believes it is ultimately about maintaining a balance, and is ever mindful that ‘it’s hard for the people living here, for older people’. ‘It’s got very commercial’, she admits, but ‘people do love it’ she goes on to validate, approving of ‘the fact that there’s wine bars, clubs, restaurants’. Comparing it to the current redevelopment of Angel, and her own neighbourhood of Highbury, Geraldine sees such progress as not only necessary but positively beneficial. ‘I know local people who would say, oh, you know, it’s terrible’, she confides, but ‘personally, I’m a 100% in favour of that’. Having thus thoroughly enjoyed this enlightening conversation with Geraldine, I hope that my account of it will prove a similarly insightful experience for readers, and offer a more nuanced perspective with which to consider Covent Garden as it is today.

This interview was conducted as part of the Lottery Heritage Fund project, 'Gentlemen We've Had Enough: the Story of the Battle to Save Covent Garden'. On 10th May 2013 King's College London students, supported by Westminster Archives, the Covent Garden Community Association, and the Centre for Life-Writing Research at King's College London, interviewed Covent Garden residents about their memories of the area. Students' accounts of their interviews have been added to this Covent Garden Memories website. For more information please see:

http://www.kcl.ac.uk/artshums/ahri/centres/lifewriting/gentlemen.aspx.'