WT Stead

Press Crusader

By Ronan Thomas

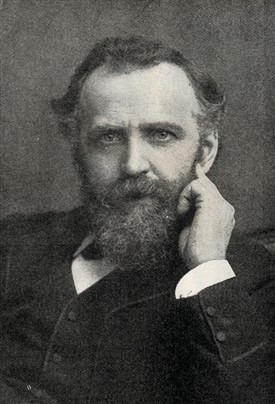

William Thomas Stead (1849-1912)

Copyright Westminster City Archives

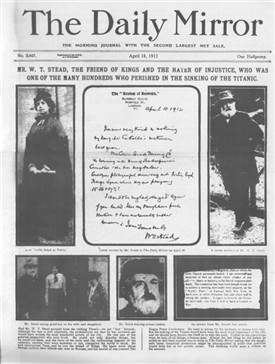

Daily Mirror front page, Titanic sinking, April 1912

Copyright Mirror Group

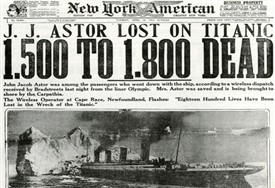

Titanic sinking front page, New York American , April 1912

Copyright Westminster City Archives

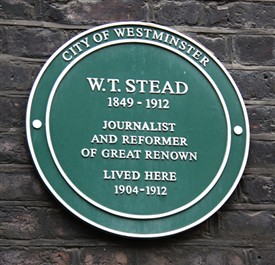

Commemorative plaque, 5 Smith Square Westminster

Copyright Westminster City Council

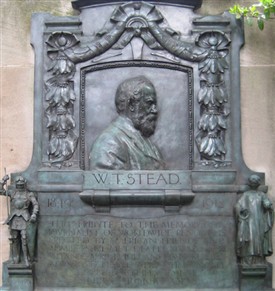

WT Stead Memorial, Victoria Embankment (1913)

Copyright Westminster City Archives

WT Stead (1849-1912) was a prominent and controversial figure in British journalism. Today, a century after his untimely death, Stead is regarded as a pioneer of investigative reporting and amongst the most innovative news editors of his age. Obsessed with exposing injustice, Stead was a tireless campaigner for social reform in Victorian Britain.

In July 1885, whilst editor of The Pall Mall Gazette, Stead ran a ground-breaking undercover expose of child prostitution in London, a case later incorporated by George Bernard Shaw into the plot of his play Pygmalion (1912). Briefly imprisoned for his pains, his efforts nevertheless pressured the government of the day into changing the law.

One hundred years on Stead’s press tactics have enduring relevance. In 2012 the UK's high-profile Leveson Inquiry into media standards and press freedoms considered the same question Stead put to Victorian society. How far should a journalist go in pursuit of a story in the public interest?

Darlington to London

William Thomas Stead was born in Embleton, Northumberland on 5 July 1849. The son of a Congregational Minister, the Reverend William Stead, he was brought up in a strictly Nonconformist family. Educated at home in Howden and then at Silcoates School, Wakefield until the age of 14, he was apprenticed to a merchant’s office in Newcastle-on-Tyne in 1863.

Evangelical by temperament and a Gladstonian Liberal by political conviction, the young Stead developed a talent for writing and soon gravitated to full-time journalism. He worked for the Darlington Northern Echo from 1871 until 1880, first as junior local reporter and then - aged only 21 - as its editor. He married in 1873, producing six children.

Stead believed he had been given a God-given purpose in life, duty-bound to use his editorial talents to promote the many Christian and other radical causes close to his heart. He felt that: ‘an editor is the uncrowned king of educated democracy’ and that the power of the press was above all: ‘an engine for social reform’. He saw himself as: ‘God’s chosen, to be His soldier against wrong’.

Such sentiments revealed much about Stead’s driven personality. Contemporary detractors in the British political and media establishment denounced his utterances as rampant egotism, but they also recognised that he possessed the mettle of principled, campaigning journalism.

Stead swiftly aligned the Northern Echo with the social causes he would champion for the rest of his life. These included: education reform (compulsory primary and secondary schooling), wider philanthropy, universal suffrage, equal pay for female journalists, better working conditions for industrial workers and collective bargaining rights.

The new editor was an ardent imperialist, in so far as he felt that the British Empire had a moral duty to spread a enlightened message to the world. He also argued for Irish Home Rule, closer relations with Tsarist Russia and the United States and anti-militarism and legal arbitration as the basis for all international relations.

In 1876 his Echo editorials thundered against Ottoman Turkey – and the Disraeli government’s initial inaction - after the former brutally crushed a Bulgarian revolt for self-determination. Next, he began a campaign to repeal the Contagious Diseases Act (1864), under which suspected prostitutes faced forced examination (it was repealed in 1886). In 1878, with his friend General William Booth, he championed social reform outside the newsroom, helping draft many of the original proposals for the new Salvation Army.

Pall Mall Gazette editor

By 1880 Stead was ready to take to a national stage. He was recruited to The Pall Mall Gazette in London, first as assistant to incumbent editor John Morley and then as editor himself from 1883-1889. The proto-tabloid Gazette - founded by Frederick Greenwood on 7 February 1865 with offices at 2 Northumberland Street WC2 - was a penny-priced evening paper strongly supportive of the Liberal Party. Along with contemporaries George Newnes (founder of the weekly compilation Tit-Bits in 1881), Alfred Harmsworth (later Daily Mail press baron Lord Northcliffe) and T.P. O’Connor (founder of The Star in 1888), Stead rode the wave of the so-called ‘New Journalism’ of the 1880s. In these years, following the literacy extension reforms of the 1870 Education Act, new penny papers - with brash reporting styles - were launched to cater to a rising British urban readership. In 1887 poet Matthew Arnold memorably described this New Journalism as ‘feather-brained’ but also ‘full of ability, novelty, variety, sensation, generous instincts’.

At the helm of The Pall Mall Gazette Stead found a ready pulpit and real social influence, using his editorship to redefine the rules of British journalism. For Stead the Gazette served as a powerful platform for the moral good of society: “The press is the greatest agency for influencing public opinion in the world…the true and only lever by which thrones and governments could be shaken and the masses of the people raised”, he opined.

Impatient for change, he redesigned the paper’s layout, adopting the short paragraphs and graphics favoured by American dailies and introducing banner headlines, illustrations, cross heads (separating long paragraphs) and reporter by-lines for the first time in British newspapers. He reduced the reprinting of political speeches, instead focusing on human interest stories and celebrity interviews, practices popularised by American newspapers since the 1830s. Amongst the Gazette’s contributors and staff were new voices such as music critic, reporter and playwright George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950). Stead and Shaw remained close collaborators and kindred spirits for over thirty years.

The Pall Mall Gazette favoured the American-inspired tactic of investigative reporting: the use of undercover reporters to generate socially beneficial publicity. Under Stead's editorship the paper undoubtedly blazed a trail for the Fleet Street daily tabloids which arose in Britain from the turn of the 20th century. The Gazette’s approach presaged the full panoply of the modern ‘gutter press’ with its lurid yet catchy headlines, door-stepping reporters and intrusive photographers. In turn this would morph into today’s image and text ‘manipulation’, hidden camera television exposes and mobile phone voicemail hacking by sections of the British media.

In his own era Stead’s hectoring, florid, reporting style and outraged tone proved the bane of governments. Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone labelled him a double-edged sword; a shrewd moral crusader but also the most damaging journalist he had ever encountered. Yet, alongside the posturing and self-promotion, Stead’s philanthropic concerns were sincerely-held. As a conviction journalist he wanted social justice and saw the Gazette as the way to get it. Campaign would now follow campaign.

Stead began his editorship of The Pall Mall Gazette with editorials condemning London's slum housing conditions. In 1883 he read a pamphlet by the Reverend Andrew Mearns, of the London Congregational Union, calling for urgent action to address the social housing crisis in the capital. Stead promptly took up the banner himself, writing a series of excoriating editorials entitled: The Bitter Cry of Outcast London. He summed up his disgust at such conditions with: ‘the man who lives by letting a pestilential dwelling-house is morally on a par with a man who lives keeping a brothel’ (The Pall Mall Gazette, 1883). In 1884 Stead also wrote The Truth about the Royal Navy, successfully lobbying for budget increases.

On 9 January 1884 Stead caused real trouble. He published an interview with Major General Charles Gordon, former Governor-General of the Sudan, castigating the Gladstone administration’s decision to pull British-backed Egyptian forces out of the country. Sudan was being threatened by Dervish rebels under the command of their charismatic leader, the Mahdi. Stead’s vitriolic Pall Mall Gazette editorials - in Gordon’s favour - drew massive publicity and forced Gladstone’s hand. Gordon got his way and was sent back to the Sudanese capital Khartoum with orders to evacuate its Egyptian garrison and European citizens. He promptly defied his remit, opting to stay and defend the city, his clear aim being to draw British forces in to occupy the country. Under public pressure Gladstone was obliged to send a relief army. But it arrived too late. On 26 January 1885, after a 10-month siege, Khartoum fell to the Mahdists and General Gordon was killed at the Governor-General’s Palace. The British press had a field day: Gladstone was blamed. The affair contributed to the fall of his second ministry on 9 June 1885.

Victorian scoop

WT Stead’s most notorious Gazette campaign was the ‘White Slavery’ case of July 1885. In conjunction with the Salvation Army he revealed that young girls could be procured to order in London and could also be exported abroad to wealthy clients. To make matters even worse, a group of corrupt doctors - guaranteeing the children’s virginity – appeared to be involved. To publicise this scandal Stead went undercover in Charles Street (today’s Ranston Street) in Lisson Grove. Posing as a well-heeled client he purchased 13 year-old Eliza Armstrong from her mother - who believed the child was destined for domestic service - for the sum of £5. Using a former prostitute as an intermediary, Stead then contrived to meet Eliza at a brothel in Poland Street W1 to prove his point.

It was an unprecedented tactic of press entrapment. Stead had his scoop and pulled out all the journalistic stops. In an advance teaser piece in the Gazette – entitled: ‘A Frank Warning’ – he dared his readers to read on. Over three evening editions, from 6-10 July 1885, the Gazette ran a series of salacious articles entitled: ‘The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’, causing a popular sensation.

London was shocked by the details. The Gazette’s offices in Northumberland Street were besieged by thousands seeking copies. In strident prose -‘the hour of democracy has come’ – Stead justified his tactics, demanding that the legal age of consent be raised from 13 to 16. Stead had pushed back the envelope of acceptable British journalism and it came at an immediate price. Because he had gained Eliza’s mother’s permission only - rather than her father’s as well – Stead had broken the law as it then stood. Along with five others he was arrested for kidnapping. Convicted at the Old Bailey in October – for the same crime he had exposed – Stead was imprisoned for three months in Holloway Prison.

He continued to edit the Gazette from his prison cell, writing ‘Government by Journalism’, an essay eulogising the moral power of the press. There were happy consequences. Under pressure from the massive publicity, the new Salisbury administration carried The Criminal Law Amendment Act (1885), increasing the age of consent from 13 to 16 and strengthening existing legislation against prostitution (it promptly became known as ‘Stead’s Act’). George Bernard Shaw would later draw on aspects of the Armstrong case as material for his hit West End play Pygmalion (1912).

International campaigner

After his release, Stead’s pursuit of radical causes continued unabated. He loudly criticised the Salisbury administration over the ‘Bloody Sunday’ riot of 13 November 1887, when London's Metropolitan Police broke up a demonstration organised by the extreme-left Social Democratic Federation (SDF). Voicing strong support for Trade Unionism he also backed a boycott of Bryant and May products as part of the Match Girl strike in 1888. Other personal enthusiasms included the employment of women as journalists on equal pay (for the first time in Fleet Street history) and a fascination with the development of new mass communication tools such as the wireless.

In 1890 Stead left the Gazette to found a new monthly digest magazine The Review of Reviews, in partnership with the Salvation Army and South African magnate Cecil Rhodes. This advocated the formation of an English-Speaking Union and the onward expansion of imperialism. The new magazine was followed by its international counterparts The American Review of Reviews (1891) and The Australasian Review of Reviews (1894).

Stead’s social agenda marched on. He assisted William Booth with the writing of his seminal work In Darkest England and the Way Out (1890), which calculated the existence of a three million-strong underclass, ‘a submerged tenth’, of the British population. The following year Stead launched the Masterpiece Library of Penny Poets, Novels and Prose Classics, designed for a working class readership keen on self-improvement. Over nine million penny novels and 5.2 million penny poetry editions were issued.

In 1893-4 he visited Chicago, witnessing its fleshpots and writing the critical ‘If Christ Came to Chicago’. In 1898 he made a journey to Russia, meeting Tsar Nicholas II as part of the International Peace Crusade (1898-1899). He created a new weekly paper ‘War against War’ and attended the Hague Conference (1899) which sought to codify the international rules of war as part of the wider Geneva Conventions (1864-1949).

Strongly opposed to militarism in all forms, Stead denounced British participation in the Second Boer War (1899-1902). In 1900 he wrote the anti-war tract ‘Shall I Slay My Brother Boer?’ prompting critics to call for his arrest for treason. He also edited ‘War Against War in South Africa’ and wrote other publications for a ‘Stop the War Committee’ set up to oppose Britain’s actions in the Transvaal. The same year he suggested forming a ‘Union International’ – a proto-United Nations - dedicated to anti-militarism, global peace and adoption of The Hague Conventions.

Presciently, in 1902 Stead also wrote ‘The Americanisation of the Twentieth Century’, warning of imperial Britain’s potential eclipse and predicting the United States’ rise to globalism. He also consistently lent his voice to calls for women’s suffrage and Irish Home Rule.

Throughout, aspects of Stead’s character continued to spark criticism and charges of eccentricity. His press rivals and many in London society increasingly viewed him as a crank. From the late 1880s Stead embraced the new language fad of Esperanto and became involved with spiritualism and the occult, founding a spiritualist journal, Borderland (from 1893-1897). His interest in spiritualism deepened after the early death of his son, Willie. His insistence on kisses from each and every female visitor to his office raised eyebrows.

In 1904, after moving into a new house at 5 Smith Square, Westminster, Stead’s professional grip began to weaken. He launched a new newspaper – The Daily Paper – but this closed at a huge loss after only six weeks. Stung by its failure, Stead travelled to Russia to report on the 1905 revolution and covered the deliberations of the second Hague Conference two years later. In early 1912 he accepted an invitation from US President Howard Taft to address a peace conference at Carnegie Hall in New York.

On 10 April 1912 Stead embarked as a First Class passenger on the maiden voyage of the White Star liner Titanic. When the ship foundered on 15 April, after hitting an iceberg in the North Atlantic, WT Stead was among over 1,500 passengers and crew to perish. Unsettlingly, Stead had predicted a maritime disaster in articles written in 1886 and 1892. Survivor accounts gave him an heroic end. He was variously reported as reading a Bible on the Titanic’s rising stern, helping passengers into the lifeboats or sitting stoically in the First Class Smoking Room. His body was not recovered.

WT Stead’s bronze memorial, unveiled on London’s Victoria Embankment in 1913, gives his epitaph: “ This memorial to a journalist of wide renown was erected near the spot where he worked for more than thirty years by journalists of many lands in recognition of his brilliant gifts, fervent spirit & untiring devotion to the service of his fellow men”.